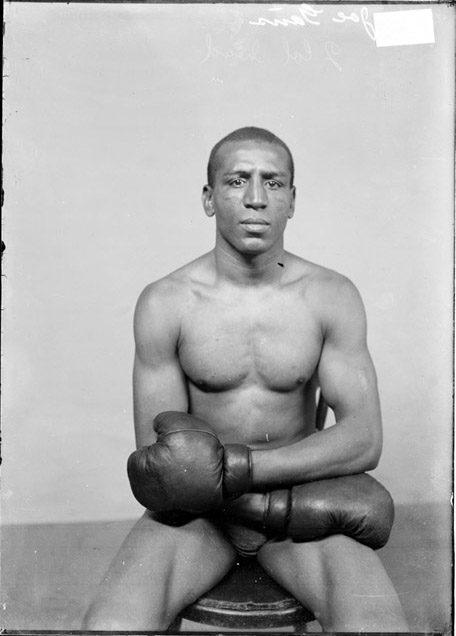

Joe Gans – “The Old Master”

By Monte D. Cox –

Joe Gans, lightweight champion of the world from 1902-1908, whose talent, polished professional style, and punching power earned him the magnificent title of “The Old Master”, was as dominate a fighter as any who ever donned gloves. Gans was a defensive master as well as a devastating puncher. He attacked vital points with pinpoint accuracy and threw every punch perfectly, in combinations and with bewildering speed. He was a master at counter punching, of the now lost art of feinting, and at the neglected art of body punching. He was a complete fighter who could be champion in any age.

Joe Gans, lightweight champion of the world from 1902-1908, whose talent, polished professional style, and punching power earned him the magnificent title of “The Old Master”, was as dominate a fighter as any who ever donned gloves. Gans was a defensive master as well as a devastating puncher. He attacked vital points with pinpoint accuracy and threw every punch perfectly, in combinations and with bewildering speed. He was a master at counter punching, of the now lost art of feinting, and at the neglected art of body punching. He was a complete fighter who could be champion in any age.

Gans great speed, power, combination punching ability and killer instinct is evident from newspaper accounts. The Sep. 28, 1904 San Francisco Chronicle reported, “Those who have watched Gans go through his work every day are amazed at his wonderful agility, his speed and his clean hitting ability.” The Jan. 20, 1906 Chronicle summed up these qualities while describing the end of his fight with the highly regarded welterweight Mike “Twin” Sullivan, “He caught Sullivan partly turned away. A dusky right arm swung over with electric quickness. A sodden glove connected with the back of Sullivan’s left ear. The Twin spun almost around from the force of the blow, and when he tried to steady himself he found that a straw colored tiger in the person of Joe Gans was upon him. Rights and lefts went with terrible swiftness to his opponents jaw. In went Gans right to the stomach, over circled his left to the jaw. And then Mike “Twin” Sullivan much the bigger and heavier man…fell backward to the canvas.”

Gans excellent footwork was described as “beautiful side-stepping, and legwork” By Nat Fleischer in Black Dynamite. The Oct 1, 1904 San Francisco Chronicle reported that “Gans beautiful footwork became evident. He was in and away or inside as it suited him best, with will-o-the-wisp elusivness.” Jack Johnson speaking of Gans footwork said, (Ring 1941, 16), “Joe moved around like he was on wheels.”

Gans was a masterful defensive fighter and counter-puncher. Against Kid McPartland, “Gans blocked his rivals leads so well it was astounding. Gans presented a beautiful defense.” Against Elbows McFadden, “He danced and ducked, countered and jabbed and simply bewildered his opponent. He was cool, calculating, shifty and blocked most of his opponents blows.” The great lightweight Jack Blackburn was “utterly unable to penetrate the champions defense” acording to the July 14, 1906 National Police Gazette. Against welterweight Mike “Twin” Sullivan, SF Chronicle Mar 18, 1906, “Gans superior cleverness at blocking saved him from any punishment and his quick counters invariably landed with great force.” Veteran boxing observer Billy Duffy agrees saying, Ring Magazine Oct 1926, that “as a counterer he was second to none.”

Gans had a remarkable ability to stop his opponent’s punches and he is considered, by many, as perhaps the best fighter ever at blocking and evading blows. Ben Benjamin wrote, Sept 7, 1907 San Fransisco Chronicle, that he “blocked blows in his incomparable style” and commented, “It is as a blocker that Gans is at his best. There never was a fighter who could block with such skill and precision as Gans. He is a perfect marvel at stopping, using either hand with equal facility. He rarely wastes a blow, his judgment on distance being almost perfect.” The August 1960 Boxing Illustrated in This was Joe Gans said, “Gans was born with a sixth sense. They tell the story of how one of his opponents, after Joe had “carried” him for six rounds, asked The Old Master, “how do you do it?” And Joe just grinned and said, “I really dunno. I tried to figure it out, but I can’t put it into words. I guess I just see what you’re thinking and when the thought gets down around the elbow I just reach out and stop it.”

The Boston Globe Sep. 2, 1906, described Gans as “one of the most wonderful fighters from a scientific view that the world has ever known. There is not a trick or point that he does not know, and he has a terrific punch with either hand. His wallops travel only a short distance and are better than the far reaching ones. Gans has a beautiful left (jab) and can do great execution with it.”

John L. Sullivan, former heavyweight champion of the world, said, St. Louis Post Dispatch, Sep. 2 1906, “I never liked a Negro as a fighting man…but Gans is the greatest lightweight the ring ever saw. He could lick them all on their best day. Gans is easily the fastest and cleverest man of his weight in the world. He can hit like a mule kicking with either hand.”

John L. Sullivan, former heavyweight champion of the world, said, St. Louis Post Dispatch, Sep. 2 1906, “I never liked a Negro as a fighting man…but Gans is the greatest lightweight the ring ever saw. He could lick them all on their best day. Gans is easily the fastest and cleverest man of his weight in the world. He can hit like a mule kicking with either hand.”

Bob Fitzsimmons declared that “Gans is the cleverest fighter, big or little that ever put on the gloves. He is also a hard hitter. He uses one hand as equally well as the other and can score a knockout with either”, Seattle Times, Sep. 2, 1906.

James W. Morrison, a referee who saw many of the greats up close, said, “Gans is careful, cool, exceptionally clever, is an excellent ring general, possessing superb footwork, and has the required punch in both hands, and can deliver it with effect at short as well as long range”, San Francisco Chronicle, Sep. 3, 1906.

McCallum in his Encyclopedia of World Boxing Champions stated, “His stance gave him perfect defense. He stood erect, hands held at chin level, ready to block and counter. He moved sparingly and his trip-hammer punches traveled only a few inches. He was a past master of feinting but couldn’t be feinted.”

William Detloff wrote, “Check out Gans knockout total, and you can see that he had the punch to compete with bigger, stronger fighters. He could hit with surprising power for one who made a Hall of Fame career out of studying and perfecting the finer nuances of the game.”

Consider Gans fight with the great Sam Langford on Dec. 8, 1903. Langford was the most avoided fighter in boxing history. Sam was the larger of the two, a natural welterweight at the time. This fight was fought in Boston the day after Gans had fought a no decision bout with black welterweight Dave Holly in Philadelphia (Gans won the newspaper decision). This means that Gans had to travel by train up the eastern seaboard from Philly to Boston for a fight the very next day. Gans admitted that fighting two days in a row and making the trip had sapped his stamina. Nevertheless, Gans dominated early in the fight before fading from lag in the later rounds and losing a close decision. Fleischer penned, (1938, 164-165; 1939, 130), “Gans opened up the first round with a triple left hook. As Sam drew back after the third blow, Gans quick as a flash, sprang forward and landed a terrific right to the jaw, and from that point until the fifth round, Langford seemed scared stiff and did his utmost to avoid infighting.”

The Boston Globe described events in the following manner, “Langford was clever and the aggressor but he had a wholesome respect for the power behind Gans right glove. And Gans proved early in the bout that his good right hand was his stock in trade and ever after that Langford managed to keep his right hand in readiness to stop any lead at which the champion might make…both blocked so well and slipped rushes so dexterously and sparred so gingerly that the bout became monotonous”, Dec 9 Globe. In other words it was a chess match. This fight is considered as the only fight the real Gans lost in a period of more than ten years. Considering it was his second fight within 24 hours in cities 300 miles apart and the quality of his opposition, Gans did very well indeed.

Gans fought welterweight champion Joe Walcott, the original, rated as the # 1 welter of all time by Nat Fleischer in 1958, to a 15 round draw which most thought Gans won. The San Francisco Chronicle called it “a grand battle as fast and furious as any ever held in a San Francisco ring”, Oct 1, 1904. According to eyewitness accounts this fight could be described as an Ali-Frazier like battle with Gans jab dominating the first rounds before the stout Walcott came on with strong body punches in the early middle rounds. In the 10th, Gans was “fast on his feet out-jabbing Walcott and not letting him get set.” The next rounds were repeats with Gans out boxing the tough Walcott. The 13th through 16th saw toe- to- toe action that was evenly fought with both fighters trying for a knockout. The last four rounds saw Gans in complete control of the tempo of the bout as he violently snapped Walcott’s head back with jabs and straight right hands, “in such a manner as it took the house by storm.” “The decision was not well received by many of the spectators who seemed of the opinion that Gans should have been favored,” Boston Globe, Oct 1, 1904.

Young Corbett, the former featherweight champion, described the Walcott fight as an eyewitness two years later, Boston Globe Sep. 1, 1906, “Walcott, the way he was a couple of years ago (before his gun accident), could have whipped any of the present crop of heavyweights. Yet out in Frisco, I saw Gans fight Walcott to a standstill. Walcott was given a draw, but it was a fierce decision. Gans mastered him and out punched him all the way.”

Gans fought the extremely clever welterweight Mike “Twin” Sullivan three times, once being outweighed by as much as 13 pounds. He scored one draw and two victories by knockout. Sullivan was knocked out only by Gans and Stanley Ketchel until the latter part of his career.

Gans met Jack Blackburn, rated the # 3 lightweight of all time by Charley Rose in 1968, three times winning once by decision over 15 rounds with two no decision bouts where Gans was clearly better. For example, in Philly on Nov. 2, 1903 Gans reportedly (Fleischer 1938, 155), “outpunched Blackburn” from start to finish.” In their other no decision contest the National Police Gazette reported, July 14, 1906, “Champion outpoints Blackburn and proves superiority.” Blackburn would go on to become a hall of fame trainer teaching Joe Louis his punching technique.

One of Gans top lightweight rivals was the hard punching Dal Hawkins, whom he met three times. San Franciscan fight promoter Jim Coffroth described Hawkins, Ring May 1943, “he was a keen, crafty, wonderful fighter and a man with the deadliest left hook that any lightweight ever carried into a prize ring.” Hawkins won by 15 round decision in their first meeting, while Gans won both rematches by devastating early round knockouts in the second and third rounds respectively.

It is clear from eyewitness accounts that Joe Gans was a complete fighter equally impressive both as an offensive puncher and as a defensive master. The available films confirm this viewpoint. The best films of Gans are the Gans-Nelson 1 fight and a battle with Kid Herman. Although the old silent films lack the technological, zoom-lensed elegance of today, Gans nevertheless looks very “modern” on film. He appears smooth and the consummate fighter. He scores knockdowns of the granite chinned Nelson with either hand. His jab is strong as an offensive as well as a defensive weapon, he is the master of ring center, elusive up close, and nearly impossible to force to the ropes. He plants his feet yet remains quite mobile and dances gracefully out of danger when necessary. Gans moves quickly on his feet to cut off Kid Herman from escaping right before he knocks him out. He throws his final debilitating right hand just like Joe Louis and it lands with similar pound for pound impact. Gans also demonstrates strong combinations and excellent hand speed, especially in the early rounds of the Nelson fight. He can take a punch if he needs to, though he is rarely hit solidly, and he fights well when hurt. His defense is impeccable intercepting his opponents leads with his rear parrying hand and then countering masterfully. One of the most impressive things about Gans is his conditioning. In the Herman film he looks completely ripped with a washboard flat stomach complete with “six-pack” abs. His arms seem huge, with big, powerful and elongated muscles. Yet he was not prone to arm weariness in long fights. His strength and punching power are quite imposing. He appears to have no weakness as a fighter.

Gans was considered as the finest lightweight in the world before he finally got a shot against lightweight champion Frank Erne, who was also considered to be among the best fighters of any weight class at that time. They met on March 23, 1900 in New York. One modern writer mistakenly said Gans was “winning easily when he suffered a cut over his eye and abruptly quit” and “it buttressed the claims of those who said the fix was in.” Not so. According to researcher Arne Steinberg Gans eye was actually protruding from his eye socket! A vicious head butt had left Gans eye hanging on his face. The Chicago Times-Herald, Mar 24, reported “Baltimore man’s eye dislodged from its socket by a head on collision.” The San Francisco Chronicle Mar 24, 1900, confirmed that, “Gans eye was started from its socket.” This was also reported by the Boston Globe. With such a horrendous injury Gans had no choice but to quit as one blow to his eye in that exposed position would have left him permanently blind.

It took Gans two years to secure a rematch, in which time he scored 22 knockouts in 32 bouts, including some 6 round no decision contests. His lone loss was a fight he threw against Terry McGovern that was one of two admitted fakes in his career, the other being the first Jimmy Britt fight. Gans went down several times against McGovern without being hit. The Dec 14 Chicago Record Herald reported that the “Bout Has Suspicious Look.” The fight’s referee George Siler, one of the best and most well known 3rd men of the period, wrote in Dec 14 Chicago Tribune “If Gans was trying last night then I don’t know much about the game.” Such uproar occurred because of the obvious dive that Chiacago’s Mayor Harrison banned boxing in the city, a ban that lasted well into the next decade.

When Joe Gans got his second shot at champion Frank Erne, on May 12, 1902, he wasted no time in gaining the title by scoring a quick knockout. Gans spent a lot of time preparing for Erne’s favorite feint and jab maneuver. Gans proved to be a master at solving an opponent’s style when he countered an intended Erne left with a perfectly timed right that sent Erne crashing to the canvas. Gans won the championship with a sensational first round knockout at 1:40 of the round.

The 1987 Ring Record Book lists Joe Gans successful lightweight title defenses at 14, the actual number may 17. In either case Gans still holds the record for the division.

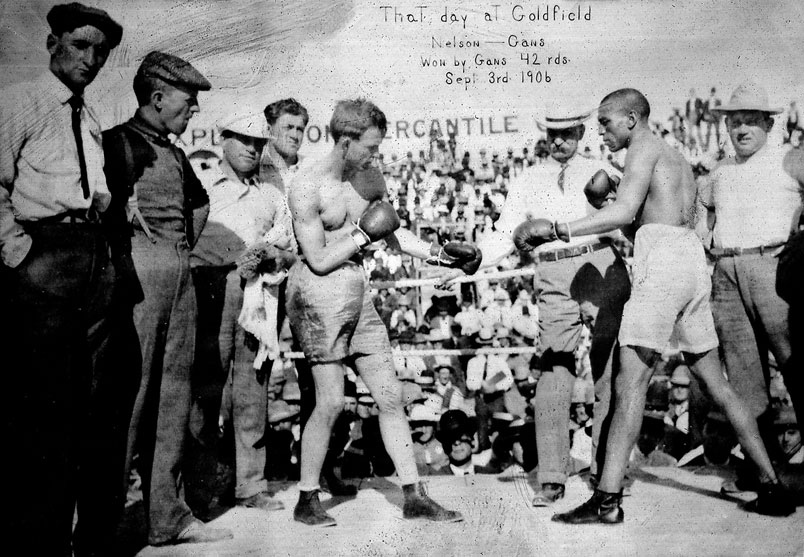

The Joe Gans-Battling Nelson fight in Goldfield, Nev. on Sep. 3, 1906 rates as the greatest lightweight championship bout ever contested. For 42 hard fought rounds the two lightweights engaged in a titanic struggle, which is the longest gloved championship match recorded under Marquis of Queensbury rules. The San Francisco Chronicle reported on Sep 4, “Dancing lightly in and away, Gans hit Nelson when and where he pleased” and described Gans as “a marvel of speed and science.” Gans scored two knockdowns and had his opponent out on his feet on two other occasions when the granite chinned Nelson was saved by the bell. In today’s fight game the fight would have been stopped long before the 42nd round when Bat purposely fouled out. Nelson absorbed a frightful beating, his left eye was closed and he was bleeding from his ears, mouth, and nose, as well as cuts on his face. Frankie Neil, a former bantamweight champion and a ringside eyewitness, said, “It looks as though Nelson, who was a very badly beaten man, took an easy way to quit”, Chronicle Sep 4, 1906.

Joe Gans was forced to fight at unnaturally low weights for much of his career. Even though he was champion he often had to succumb to the dictates of his white opponents. Gans had trouble making 133 pounds ringside several times. If he were fighting today he would be a natural 140-pound fighter, though since he would not have to make weight ringside, he could easily make the 135-pound limit. In the first Nelson fight he was forced to make 133 ringside in full gear, this combined with the dehydrating Nevada sun and the grueling 42 round fight may have contributed to Gans contracting Tuberculosis (TB), which was one of the leading causes of death in that day.

Gans began to suffer from TB by at least 1908. TB is an infection disease that affects the lungs and causes difficulty in breathing with symptoms such as weakness and fatigue, chilling, chest pain, and sometimes coughing blood. The Greeks called tuberculosis “consumption” because it caused a total destruction of the body.

Gans was certainly suffering from the ravaging affects of tuberculosis by the time he lost the title in a rematch to Battling Nelson on July 4, 1908. The San Francisco Chronicle described Gans as “weakened and dull in the eyes” and said, “It was clear that it was a different Gans than the one who had fought at Goldfield.” Even more revealing was the report that “After the twelfth round Gans was suffering terribly. His skin turned a dull gray and he was shivering as though from ague” (fever). “It seemed as though his vitality had been stolen from him”, Chronicle July 5th. Those are obvious signs of tuberculosis disease. Despite this the “first five rounds were Gans by a wide margin”. In the second round an uppercut staggered Nelson, in the third Gans drew blood. However he was so weakened by the disease that was killing him that he began to fade. Despite being desperately sick Gans fought on before succumbing as he said “to exhaustion” in the 17th round. Amazingly had it been a 15 round fight he would have made the distance. Certainly no one could ever question his courage.

Gans and Nelson fought again two months later. Gans made it 21 rounds this time a feat of will and strength that defies logic and reason. He again dominated the early rounds with well-timed and accurate punches. For the first few rounds Gans looked like the master of old. He used “clever ducking, and sidestepping, jabbing and sharp shooting”. But eventually the Dane’s fierce body punching wore down Gans sickly form. In both fights under modern rules Gans would have made the distance and perhaps even won in a 12 round bout, especially in the second fight. Nelson commented, “Gans gave me a tougher fight this time. Gans was certainly a game boy and took a lot of a beating”, Chronicle Sep 10, 1908.

Gans fought one more time against former British champion Jabez White. “Even though his body was full of death germs, Gans still displayed some of his famous punching power” wrote Fleischer. The New York Daily Herald reported, “The way Gans boxed the sixth round it looked like he meant business. He let loose a right and Jabez went down flat. He arose at the count of nine. Gans hooked up another right to White’s jaw and down he went again. This time he looked out for good, but the bell saved him.” In the seventh he “popped an uppercut to Jabez’s chin. The Briton was knocked out this time. But again the bell saved him.” “He dropped him once more in the eighth” (Herald, Mar 13, 1909). Gans actually knocked out White twice in that 10 round fight. It was officially a no decision bout but Gans easily won the newspaper verdict. The following year Gans died in his mother’s arms. When he died he only weighed 84 pounds.

Joe Gans record according to the Boxing Register, the official Hall of Fame record book, is 120-8-9 (85 kayo’s) 18 No Decisions. Historian Gilbert Odd wrote that because of the hostile attitude towards black fighters Gans “often had to box to orders”. McCallum wrote that “he frequently climbed into the ring handcuffed” forced often by promises to gamblers and opponents managers to carry his opposition. Virtually all of his draws and no decisions were battles that he actually won. One must consider that Gans was the first black -American born- boxing champion, and he often suffered from racial prejudice and injustice and was sometimes forced to carry and even lose to white opponents. Willie Ritchie, lightweight champion from 1912-1914, who knew Gans, said in an interview with Peter Heller, “Gans had to do as he was told by the white managers. They were crooks. They framed fights, and being a Negro the poor guy had to follow orders, otherwise he’d have starved to death.”

Joe Gans deserves to be rated among the elite of the greatest pound for pound fighters of all time. Nat Fleischer rated Gans as the # 1 All Time Lightweight in 1958. Charley Rose considered Gans as the # 2 lightweight of all time in 1968 behind Benny Leonard. Herb Goldman rated him as the # 3 Lightweight of all time in 1987. Tad Dorgan, a boxing commentator and writer for the San Francisco Chronicle and New York Journal, who saw all the greats from James J. Corbett to Gene Tunney, rated Joe Gans as the greatest fighter he ever saw regardless of weight. Thomas S. Rice, of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, also rated Gans as the greatest lightweight ever. Jimmy Coffroth, the great San Francisco fight promoter, who saw many of the greats up until the time of his death in 1943 rated Gans as the king of all lightweights. McCallum in his “Survey of Oldtimers” 1975, has Gans rated as the # 1 all time lightweight. William Detloff rated Gans among the 20 greatest fighters of the 20th century in 2000.

In this writers opinion Joe Gans is the greatest lightweight of all time ahead of Benny Leonard, Roberto Duran, Henry Armstrong and Pernell Whittaker.