The Legend of John L. Sullivan

By Joe Torcello –

You might say John L. Sullivan is to boxing what George Washington is to the presidency. He was the first in a historical lineage of personalities and title holders that would shape the face of the sport. He was considered by most boxing historians to be the first to hold what was once called – “The Greatest Title in Sports,” as the heavyweight champion of the world.

You might say John L. Sullivan is to boxing what George Washington is to the presidency. He was the first in a historical lineage of personalities and title holders that would shape the face of the sport. He was considered by most boxing historians to be the first to hold what was once called – “The Greatest Title in Sports,” as the heavyweight champion of the world.

Today, many boxing fans think of Sullivan as the aging, out-of-shape, one-dimensional slugger who stepped into the ring against Jim Corbett in 1892. That would be the equivalent of reading a book by starting with the last chapter.

THE BAREKNUCKLE ERA

Before the Marques of Queensberry rules and the gloved-era, Sullivan pounded out his reputation as “The Boston Strong Boy” – bludgeoning numerous opponents into unconsciousness in what some historians have estimated to be hundreds of illegal, bare-knuckle fights.

Sullivan lived life as many champions throughout the years have – at full throttle. Women, booze and brawls are probably an accurate summation of the man and his lifestyle during the prime years of his life. A family man he was not.

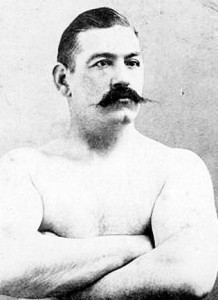

John L was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts on October 15, 1858. Sullivan stood 5 feet, 10 ½ inches tall (short by today’s Heavyweight standards) and weighed approximately 200-pounds. in his prime. By all historical accounts, he possessed brute strength as well as surprising hand speed.

“His right arm comes across like a flash of lightning with a jerk. And if he misses, he’s so quick you can’t get your head out of range before it’s back ready for another shot at your jaw.”

– Joe Choynski – Heavyweight Contender

Make no mistake about it; John L. Sullivan enjoyed fighting. You don’t walk into a saloon or bar and announce, “I can lick any sonafabitch in the house!” if you don’t enjoy fighting!

THE SULLIVAN LEGEND

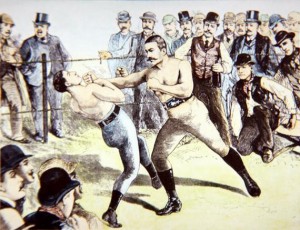

In total, some historians believe Sullivan to have been victorious in well over 200 fights. This number includes the many bare-knuckle fights fought under the London Prize Ring Rules. Under the London rules, bouts were held in a 24-ft square “ring” enclosed by ropes. A knockdown ended the round, followed by a 30-second rest and an additional 8 seconds to regain the center of the ring or lose the fight. Butting, gouging, hitting below the waist, and kicking were banned. The fight ended when either one of the fighters was knocked out or neither could continue.

It was during this time to Sullivan legend was born.

Sullivan claimed the title of heavyweight champion of American in 1882 against Paddy Ryan after stopping him in nine rounds.

Sullivan claimed the title of heavyweight champion of American in 1882 against Paddy Ryan after stopping him in nine rounds.

Afterwards, Ryan said, “When Sullivan hit me, I thought a telegraph pole had been shoved against me endways.”

The following description was taken from the New York Daily Tribune – dated February 8, 1882;

_ Ninth Round – Ryan failed to come to time and the fight was declared in favor of Sullivan. Ryan and Sullivan were visited after they had gone to their quarters. Ryan was lying in an exhausted condition on his bed, badly disfigured about the face, his upper lip being cut through and his nose disfigured. He did not move but lay panting. Stimulants were given him. He is terribly

punished on the head. At the conclusion of the fight Sullivan ran laughing to his quarters at a lively gait. He lay down

awhile as he was a little out of wind, but there is not a scratch on him. He chatted pleasantly with his friends.

_ The fight was short, sharp, and decisive on Sullivan’s part throughout, Ryan showing weariness after the first round.

Paddy Ryan was considered the champion when he captured the title two years earlier from Joe Goss in Collier’s Station, West Virginia. Goss succumbed to Ryan after 87 rounds of punishment. As an interesting side note, Goss had the pleasure of being in Sullivan’s corner for his victory over Ryan.

Like most fighters, John L also had an opponent whose style gave him all kinds of problems. That opponent was Englishman named Charlie Mitchell. Mitchell was a “runner” when it came to Sullivan. Sullivan may have had fast hands; his feet weren’t nearly as swift as Mitchell’s.

(Side note: Mitchell, a middleweight, fought in the bare-knuckle and gloved-era. He would eventually face Sullivan conqueror Jim Corbett, only to get knocked out in the third round. In the earlier years, however, he was an awkward and powerful fighter.)

Mitchell challenged Sullivan to a three-round bout in Madison Square Garden in New York City. Sullivan started fast and dropped Mitchell twice in the opening round. Then, lightning struck when Mitchell countered Sullivan with a left hook to the chin that dropped him for the first time in his career. John L was more enraged than anything else and tore into Mitchell in the second and third rounds. He hurt Mitchell badly, but Mitchell hung on until the Police stopped the fight after the third round. The bad blood between the two had been established.

THE NEW YORK POLICE GAZETTE

Richard K. Fox, the publisher of the New York Police Gazette (the Ring Magazine of its day), wasn’t a fan of Sullivan’s. Sullivan snubbed Fox after defeating Paddy Ryan, who was a protégé of Fox. You might say Fox made it his mission to find a fighter who would lift Sullivan’s title and hand the champion his first defeat.

Fox imported a 236-pound Herbert A. Slade from New Zealand. The fight was set for Madison Square Garden. Slade found himself on the floor multiples time during the first two rounds. He was rescued with the police stopped the mismatch in the 3rd.

In September of 1883, Sullivan began touring in Baltimore. Over the course of a year, Sullivan fought 154 men in four round bouts. The deal was, if he were unable to knock out an opponent, he would give up $1,000. He knocked out all 154 opponents! A month after the tour ended, he was matched once again against his rival Charlie Mitchell.

Sullivan showed up drunk to the fight and wasn’t in any condition to defend the title. News of Sullivan’s drinking problems spread across the country. His manager, Al Smith, quit. What followed became a familiar pattern of drinking and defending his title against “Tomato Can” opponents. Even so, John L’s popularity was amazing. People would gladly part with their hard-earned money to say they’d seen the great John L. Sullivan in person.

Sullivan knocked out his old foe, Paddy Ryan in one round at Madison Square Garden in 1885. In August of the same year, he defeated Dominick McCaffrey on points over 7-rounds and was named the first Heavyweight Champion under the Marques of Queensberry Rules.

In 1887, Sullivan traveled to London to box and exhibition for the Prince of Wales (who later became King Edward VII). Charlie Mitchell wasted no time and began taunting Sullivan saying that he’d knocked Sullivan down during their first meeting and Sullivan was afraid to fight him again. Finally, Sullivan couldn’t take Mitchell’s taunts any longer and agreed to fight him. Prize fighting was still illegal in those days, but they found a way around it nonetheless thanks to Baron Rothschild of the infamous Rothschild banking family.

Rothschild arranged for the fight to take place at his racing stables in Chantilly, France on March 10, 1888. The fight was a “by invitation only” event. The fight took place outside, in the middle of the pouring rain. Sullivan started quickly. Mitchell danced around and avoided his rushes. The fight finally ended in the 39th round when the police were spotted. The fight was declared a draw. Other accounts of the fight say that both men were exhausted – Mitchell from running and Sullivan from chasing.

Sullivan returned to Boston on April 24, 1888. His drinking was getting out of control and he was rapidly gaining weight. By the summer, he was experiencing serious physical symptoms and believed he was going to die. He was thirty-years old. Sullivan retreated to his father’s house and a priest was summoned to administer last rites. His liver and stomach were swollen and inflamed and an intense fever had taken hold. Incredibly, he survived. A month later, he recovered after losing 80-pounds.

During this time, Richard K Fox was determined to find and officially recognize a “new” champion of the world. One who took on serious challengers and was in his fighting prime. He chose the undefeated Irish-American heavyweight – Jake Kilrain. In May 1887, Fox presented him with a silver championship belt on behalf of the National Police Gazette.

Sullivan supporters were outraged. In Boston, Sullivan’s backers and fans presented him with a championship belt made of 14-carat gold. The belt had eight panels with scenes depicting Sullivan along with symbols and the flags of the United States, England, and Ireland. In the middle by a large shield with the engraving, “Presented to the Champion of Champions, John L. Sullivan, by the Citizens of the United States.”

Sullivan supporters were outraged. In Boston, Sullivan’s backers and fans presented him with a championship belt made of 14-carat gold. The belt had eight panels with scenes depicting Sullivan along with symbols and the flags of the United States, England, and Ireland. In the middle by a large shield with the engraving, “Presented to the Champion of Champions, John L. Sullivan, by the Citizens of the United States.”

There were 397 diamonds in total spelling out his name. A proud John L Sullivan referred to Kilrain’s belt as a dog collar in comparison.

John L and Jake Kilrain, a battle of the undefeated “champions” took place on July 8, 1889 at Richburg, Mississippi. With the help of William Muldoon, a wrestler and physical training “guru” of the day, Sullivan (for the first time in his career) trained under the guidance and oversight of a professional. Sullivan was quoted as saying, “A fellow would rather fight twelve dozen times than train once,” he said. “But it has to be done.”

The fight would be the last fight ever fought under the London Prize Ring Rules. The purse was $10,000, winner take all. The training of Muldoon had transformed a tired, bloated 240-pound Sullivan into a hard, chiseled, 215-pounds.

The battle which took place within the scorching summer heat, affected Kilrain more than it did Sullivan. After two hours and 75 rounds later, Kilrain’s corner was told by a doctor that Kilrain’s life would be in jeopardy if he endured anymore punishment. Kilrain was exhausted and barely conscious.

The telegraph immediately sent word of Sullivan’s victory to newsrooms throughout America. Even Richard K Fox finally admitted, “By this fight, Sullivan has proved that he is a first-class pugilist in every respect. He is a stayer as well as a slugger.”

After the Kilrain fight, John L fell back into his former lifestyle and began drinking heavily once again. He announced that he would run for Congress but failed to obtain the backing of the party. His heavy drinking and frequent public brawling ended his days as a politician before they began. Sullivan had no intensions of fighting again. Unfortunately, as would be the case in the lives of many champions to come, Sullivan just could not part with the “living large” lifestyle and all the extras that went with it.

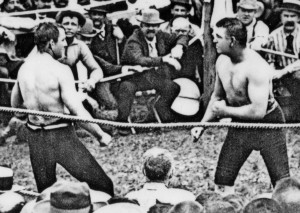

Once again, Sullivan would have to step back into the ring. On September 7, 1892, an aging, flabby Sullivan (who parted ways with his trainer Muldoon) stepped into the ring with top contender James J. Corbett who was eight years younger at 26. The fight took place at the Olympic Club in New Orleans, Louisiana. In New Orleans, prize fights were legal under the Marquis of Queensbury rules.

Corbett won the World Heavyweight title by knocking out Sullivan in the 21st round. Corbett’s new scientific boxing technique enabled him to dodge John L’s rushing attacks and wear him down with jabs. A combination of rights and lefts put Sullivan down for the ten count and Sullivan’s undefeated run had finally come to an end. After the fight, Sullivan gave a teary-eyed farewell speech and left the world stage more beloved than ever before.

Now outside the ring once again, Sullivan’s drinking problems resumed. The drinking also opened to doors to a variety of legal problems including assault.

In late 1905 Sullivan became a changed man. His demons finally behind him, he became an evangelist and married a childhood sweetheart in 1910. He toured the United States speaking out against the evils of alcohol and became a very popular speaker and lecturer. On the morning of February 2nd 1918, Sullivan died of a heart attack at the age of 60.